After the fire

Helderberg Nature Reserve has been a special place to me for more than half my life, starting after my freshman year of college, in Walla, Walla, Wash., when I decided to strike out to see the world. Some of my friends were heading to Europe. But I was interested in Africa.

Education comes first, that’s what my parents always told me. So I found a college in South Africa with transferable credits back to the United States, and used it as my base camp. The campus was situated on the lower slopes of Helderberg Mountain, wedged between a winery on the west and the nature reserve on the east. The reserve was traversed with easy trails, but the surest way to enjoy a quiet day off campus was to head up to the top. Helderberg Mountain has not just one but three peaks, each higher than the last, with varying superb views of False Bay below, and — far in the distance — Table Mountain with its wispy crown of clouds and a barely visible Cape Town at its feet.

Fast forward to October 2023. I had seen the many moods of Helderberg Nature Reserve, but never like this. The proteas were blackened sticks burned out by a fire that had swept through in June. But even now, just four months later, the charred fynbos was regenerating like it has for millennia. I was genuinely surprised to see so many flowers in bloom six weeks later into the summer than usual. But it’s been a very wet year, I learned.

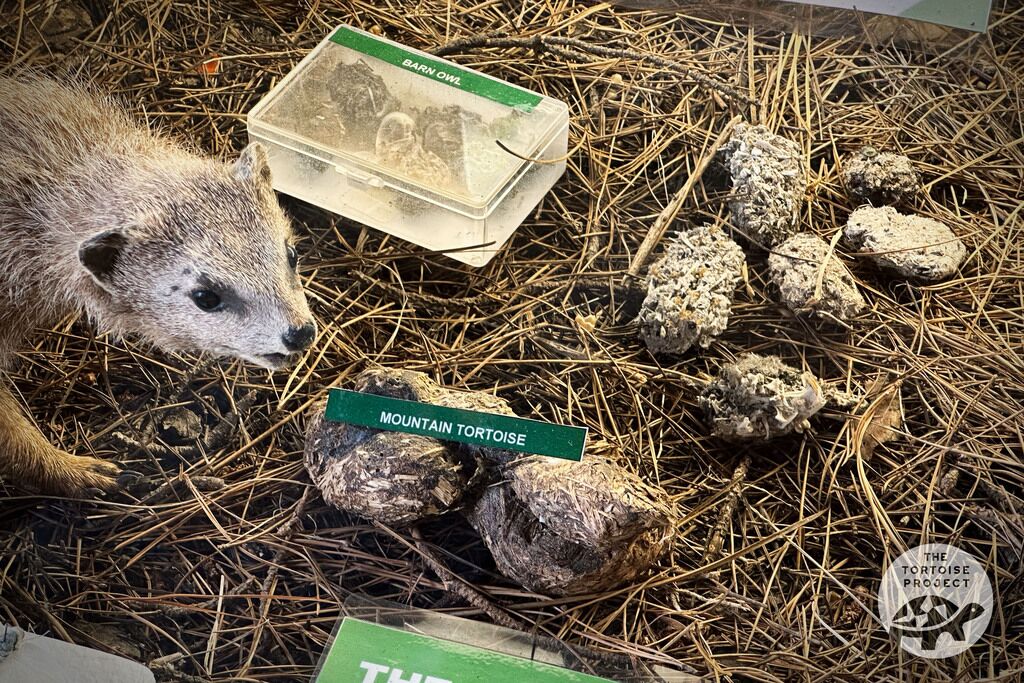

The little museum held a treat for me: a display case like what you might see at the ranger station of a state park in the United States. Artfully arranged among the stuffed animals and insects were the empty shells of two species of tortoises found within the reserve, the Angulate tortoise (Chersina angulata) and the Parrot-beak tortoise (Homopus aerolatus). As an extra bonus, the case held a scat sample donated by an anonymous Leopard tortoise (Stigmochelys pardalis) which isn’t native to the Western Cape but was introduced to the region from other parts of South Africa by humans … and it’s thriving.

Here are some of the wildflowers I found in bloom.